1 + 12As we prepare for the next round of intensives, this material may change.

In this first workshop we will cover

Python is a programming language that can be used to build programs (i.e. a “general programming language”), but it can also be used to analyse data by importing a number of useful modules.

We are using Spyder to interact with Python more comfortably. If you have used RStudio to interact with R before, you should feel right at home: Spyder is a program designed for doing data science with Python.

Python can be used interactively in a console, or we can build scripts and programs with it, making the most out of Spyder’s code editor.

We will start by using the console to work interactively. This is our direct line to the computer, and is the simplest way to run code. Don’t worry about any unfamiliar language, fonts or colours - we can ignore most of it for now - all you need to know is that

In [1]: ... is code that we’ve sent to the computer, andOut[1]: ... is its response.To start with, we can use Python like a calculator. Type the following commands in the console, and press Enter to execute them:

After running each command, you should see the result as an output.

Like language, Python has nouns and verbs. We call the nouns variables: they are the ‘things’ we manipulate with our code.

Essentially, a variable is a named container. We access it by its name, and we get its value.

To create a variable, you need to choose a name and a value with name = value. For example

Whenever you use the variable’s name, Python will now access its value:

We can use the variables in place of the values

Spyder helps us with extra panels and features apart from the Console. To see what variables you have created, look at the “Variable explorer” tab in the top right.

Variables have different types. So far, we’ve just looked at storing numbers, of which there are three types:

int - integers store whole numbers, e.g. 1, 5, 1000, -3.float - floating point numbers store decimals and scientific notation, e.g. 1.5, -8.97, 4e-6.complex - complex numbers express the imaginary unit with j, e.g. z = 1+2j is \(z = 1+2i\).Let’s look at some other types

Even simpler than integers is the boolean type. These are either 1 or 0 (True or False), representing a single binary unit (bit). Don’t be fooled by the words, these work like numbers: True + True gives 2.

In Python, the boolean values

TrueandFalsemust begin with a capital letter.

Let’s look at variable types which aren’t (necessarily) numbers. Sequences are variables which store multiple pieces of data. For example, strings store a sequence of characters and are created with quotation marks 'blah blah blah' or "blah blah blah":

We can also create lists, which will store several variables (not necessarily of the same type). We need to use square brackets for that:

Lists are very flexible as they can contain any number of items, and any type of data. You can even nest lists inside a list, which makes for a very flexible data type.

Operations on sequences are a bit different to numbers. We can still use + and *, but they will concatenate (append) and duplicate, rather than perform arithmetic.

[38, 3, 54, 17, 7, 38, 3, 54, 17, 7, 38, 3, 54, 17, 7]However, depending on the variable, some operations won’t work:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[12], line 1 ----> 1 example_string + example_int TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

There are other data types like tuples, dictionaries and sets, but we won’t look at those in this session. Here’s a summary of the ones we’ve covered:

| Category | Type | Short name | Example | Generator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numeric | Integer | int |

3 |

int() |

| Numeric | Floating Point Number | float |

4.2 |

float() |

| Numeric | Boolean | bool |

True |

bool() |

| Sequence | String | str |

'A sentence ' |

" " or ' ' or str() |

| Sequence | List | list |

['apple', 'banana', 'cherry'] |

[ ] or list() |

The generator commands are new. We use these to manually change the variable type. For example,

yields 1, converting a boolean into an integer. These commands are functions, as opposed to variables - we’ll look at functions a bit later.

We can access part of a sequence by indexing. Sequences are ordered, starting at 0, so the first element has index 0, the second index 1, the third 2 and so on. For example, see what these commands return:

If you want more than one element in a sequence, you can slice. Simple slices specify a range to slice, from the first index to the last, but not including the last. For example:

That command returns elements from position 0 up to - but not including! - position 4.

So far, we’ve been working in the console, our direct line to the computer. However, it is often more convenient to use a script. These are simple text files which store code and run when we choose. They are useful to

Let’s create a folder system to store our script in by creating a project.

Projects > New project... and name your project, perhaps “python_training”.File > New file... or the new file button.You should now see a script on the left panel in Spyder, looking something like this:

Try typing a line of code in your new script, such as

Press F9 to run each line, or ctrl+enter for the whole script. You should see something like the following appear in the console (depending on how you ran it):

We’ll work out of a script for the rest of the session. Don’t forget to save your script by pressing ctrl+S or the save button. )

Functions are little programs that do specific jobs. These are the verbs of Python, because they do things to and with our variables. Here are a few examples of built-in functions:

6Functions always have parentheses () after their name, and they can take one or several arguments, or none at all, depending on what they can do, and how the user wants to use them.

Here, we use two arguments to modify the default behaviour of the round() function:

Notice how Spyder gives you hints about the available arguments after typing the function name?

Operators are a special type of function in Python with which you’re already familiar. The most important is =, which assigns values to variables. Here is a summary of some important operators, although there are many others:

| Operator | Function | Description | Example command |

|---|---|---|---|

= |

Assignment | Assigns values to variables | a = 7 |

# |

Comment | Excludes any following text from being run | # This text will be ignored by Python |

| Operator | Function | Description | Example command | Example output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

+ |

Addition | Adds or concatenates values, depending on variable types | 7 + 3 or "a" + "b" |

10 or 'ab' |

- |

Subtraction | Subtracts numerical values | 8 - 3 |

5 |

* |

Multiplication | Multiplies values, depending on variable types | 7 * 2 or "a" * 3 |

14 or 'aaa' |

** |

Exponentiation | Raises a numerical value to a power | 7 ** 2 |

49 |

/ |

Division | Divides numerical values | 3 / 4 |

0.75 |

// |

Floor division | Divides numerical values and then rounds down | 3 // 4 |

0 |

% |

Remainder | Takes the remainder of numerical values | 13 % 7 |

6 |

| Operator | Function | Description | Example command | Example output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

== |

Equal to | Checks whether two variables are the same and outputs a boolean | 1 == 1 |

True |

!= |

Not equal to | Checks whether two variables are different | '1' != 1 |

True |

> |

Greater than | Checks whether one variable is greater than the other | 1 > 1 |

False |

>= |

Greater than or equal to | Checks whether greater than (>) or equal to (==) are true | 1 >= 1 |

True |

< |

Less than | Checks whether one variable is less than the other | 0 < 1 |

True |

<= |

Less than or equal to | Checks whether less than (<) or equal to (==) are true | 0 <= 1 |

True |

To find help about a function, you can use the help() function, or a ? after a function name:

Help on built-in function max in module builtins:

max(...)

max(iterable, *[, default=obj, key=func]) -> value

max(arg1, arg2, *args, *[, key=func]) -> value

With a single iterable argument, return its biggest item. The

default keyword-only argument specifies an object to return if

the provided iterable is empty.

With two or more arguments, return the largest argument.

In Spyder, you can use the Ctrl + I keyboard shortcut to open the help in a separate pane.

For a comprehensive manual, go to the official online documentation. For questions and answers, typing the right question in a search engine will usually lead you to something helpful. If you can’t find an answer, StackOverflow is a great Q&A community.

Python, on its own, requires a lot of manual programming for advanced tasks. What makes it versatile is the capacity to use other people’s code with modules.

To bring in advanced variables and functions that other’s have made, we need to import the module. For example

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- NameError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[20], line 1 ----> 1 pi NameError: name 'pi' is not defined

returns an error, because it’s undefined. But the math module contains a variable called pi:

To access objects from within a module, we use a full stop:

module.object_inside.

Arrays are a data type introduced by numpy, a module with many functions useful for numerical computing.

For example, you can convert the list we created before to then do mathematical operations on each one of its elements:

pandas introduces dataframes, which are often used to store two-dimensional datasets with different kinds of variables in each column. If your data is stored as a spreadsheet, you probably want to import it with a pandas function.

First, we’ll need to install and import the pandas module. Install it as before (either with pip or conda), and then run

Now, let’s import some data to get ready for the next session.

datadata folderpd.read_csv() to load the data:You’ll see that it’s now in your variable explorer. You can double-click on a dataframe in the Variable explorer to explore it in a separate window.

We’ll look at manipulating these dataframe objects in the next session. For now, try running the df.head() function to examine the first few rows:

| name | birth_date | height_cm | positions | nationality | age | club | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | James Milner | 1986-01-04 | 175.0 | Midfield | England | 38 | Brighton and Hove Albion Football Club |

| 1 | Anastasios Tsokanis | 1991-05-02 | 176.0 | Midfield | Greece | 33 | Volou Neos Podosferikos Syllogos |

| 2 | Jonas Hofmann | 1992-07-14 | 176.0 | Midfield | Germany | 32 | Bayer 04 Leverkusen Fußball |

| 3 | Pepe Reina | 1982-08-31 | 188.0 | Goalkeeper | Spain | 42 | Calcio Como |

| 4 | Lionel Carole | 1991-04-12 | 180.0 | Defender | France | 33 | Kayserispor Kulübü |

matplotlib is a large collection of data visualisation functions, and pyplot is a submodule of matplotlib that contains essentials.

This shows a plot in the Plots tab of Spyder.

If your plots aren’t appearing, then it might be due to a known bug. The latest versions of Spyder and matplotlib solve the problem, but we can apply a fix locally for now.

Step 1.

Check that it’s not a different issue. If you see any error message, then this bug is not the problem - you should solve the error first.

Assuming there is no error message, this bug is featuring if

To apply a quick fix (and ensure that the plots are otherwise ok), try running

This won’t fix the problem, but it will let you manually see the plots.

Step 2.

Before you try to fix the issue manually, updating Spyder to the latest version should solve the issue.

Once it’s done, relaunch Spyder and give it a go.

Step 3.

There are three ways which might fix the bug if you can’t update Spyder. The first is to run

Try running the plot again. If it works, great!

If it doesn’t work, try

If that doesn’t work, then you should adjust your Spyder settings.

Try running your plots again.

Step 4. If they still aren’t working, then ask a trainer for assistance.

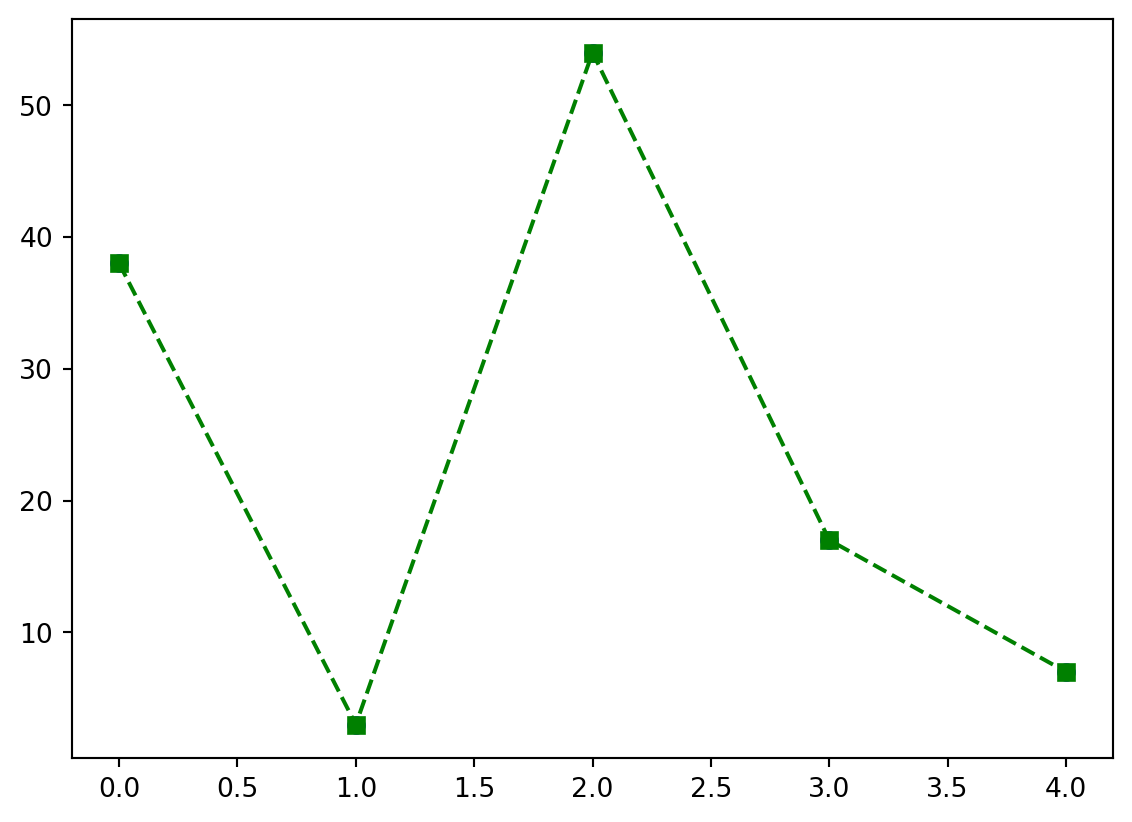

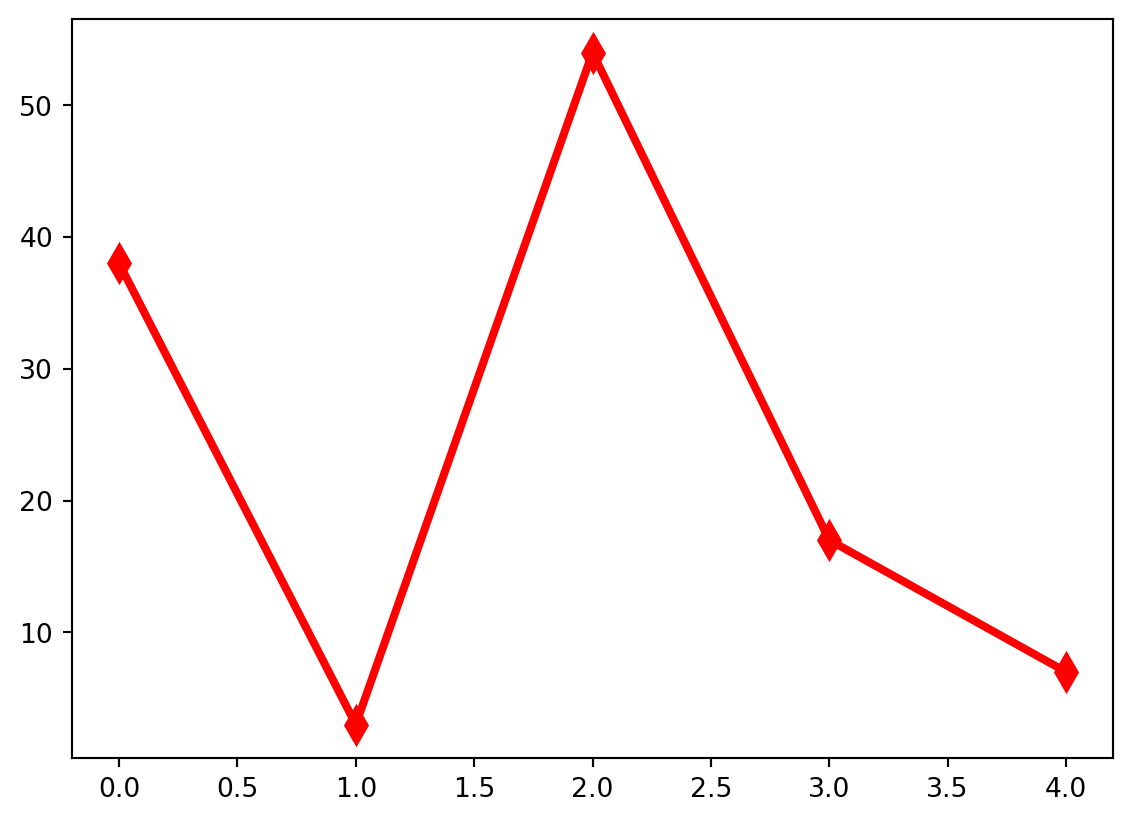

The default look is a line plot that joins all the points, but we can style a plot with only a few characters:

Extra arguments can be used to style further:

To find out about the styling shorthand and all other arguments, look at the documentation:

The math module is built-in - the module came when I installed Python, and the numpy, pandas and matplotlib come with conda installations. Most other modules live online, so we need to download and install them first.

Installing modules depends on whether you have a conda environment or not. To check, run

| Message | conda Environment? |

|---|---|

conda is a tool for managing and deployi... or something similar |

Yes |

NameError: name 'conda' is not defined |

No |

You can install packages with

You likely have a conda environment if you installed Anaconda or you installed Spyder 6 (Since Oct 2024)

You can install packages with

You likely have a pip environment if you installed Python manually or are using an older (before Oct 2024) version of Spyder (e.g. Spyder 5)

One module that isn’t built-in is plotly, which we can use for interactive visualisations.

Press “Save” or Ctrl + S to save your script.

Your project can be reopened from the “Projects” menu in Spyder.

By default, your variables are not saved, which is another reason why working with a script is important: you can execute the whole script in one go to get everything back. You can however save your variables as a .spydata file if you want to (for example, if it takes a lot of time to process your data).

This morning we looked at a lot of Python features, so don’t worry if they haven’t all sunk in. Programming is best learned through practice, so keep at it! Here’s a rundown of the concepts we covered

| Concept | Desctiption |

|---|---|

| The console vs scripts | The console is our window into the computer, this is where we send code directly to the computer. Scripts are files which we can write, edit, store and run code, that’s where you’ll write most of your Python. |

| Variables | Variables are the nouns of programming, this is where we store information, the objects and things of our coding. They come in different types like integers, strings and lists. |

| Indexing | In order to access elements of a sequence variable, like a list, we need to index, e.g. example_numbers[2]. Python counts from 0. |

| Functions | Functions are the verbs of programming, they perform actions on our variables. Call the function by name and put inputs inside parentheses, e.g. round(2.5) |

| Help | Running help( ... ) will reveal the help documentation about a function or type. |

| Packages | We can bring external code into our environment with import .... This is how we use packages, an essential for Python. Don’t forget to install the package first! |